A new face of the Democratic Party emerges: Black progressives

(CNN) — Progressive Democrats are poised to claim a series of historic successes in congressional races decided during nationwide uprising over racial injustice and inequality.

The unexpected revival was keyed by Black candidates in New York, Virginia and Kentucky, who are either leading their contests or running remarkably close in challenges they were almost uniformly expected to lose from the beginning.

Those performances have not only reanimated a leftist insurgency that seemed to be waning as former Vice President Joe Biden became the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, but underscored what many activists had been discussing for months: That the future of the movement would be charted by candidates of color, and others from marginalized communities, who could speak fluently about the intersection of race and class, and whose life experiences more closely reflected those of the voters they were running to represent.

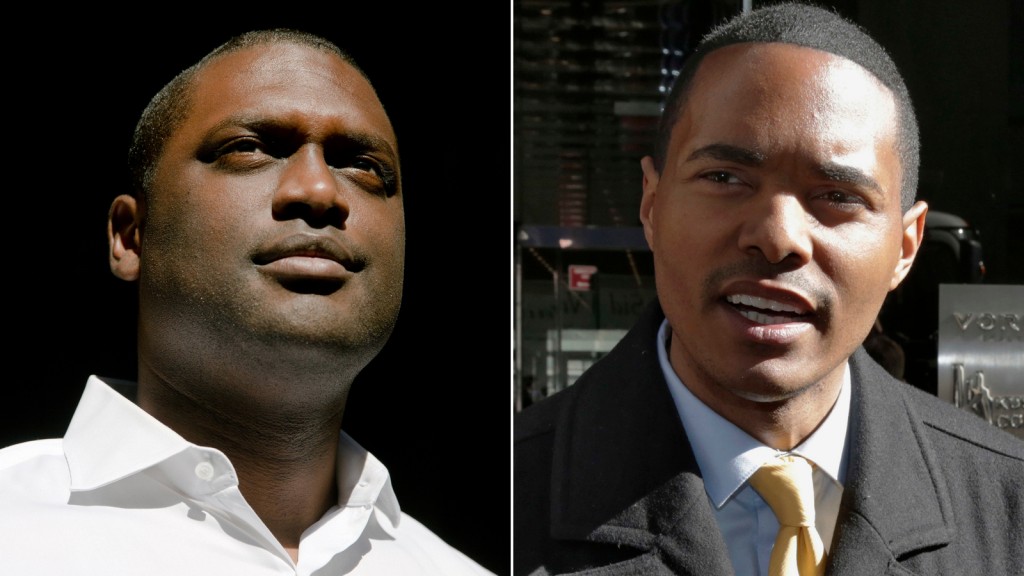

In New York, a Democratic stronghold with an aging congressional delegation, the signature showings were authored by Jamaal Bowman, a 44-year-old Black former educator, and Mondaire Jones, 33, a Black man who is gay. If their leads hold, Bowman and Jones would replace Rep. Eliot Engel, a self-described member of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s “kitchen cabinet,” and retiring Rep. Nita Lowey — the state delegation’s two longest serving current members. City Councilman Ritchie Torres, who is gay and the son of Black and Puerto Rican parents, is also ahead in his race to takeover Rep. Jose Serrano’s seat in a nearby district. If Jones and Torres win in November, they will be the first out gay Black congressmen in US history.

“The future of the Democratic Party looks a lot more like (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) and Jamaal than Joe Biden. The constituencies now leading grassroots movements will only become more essential to the Democratic Party’s future,” Justice Democrats communications director Waleed Shahid said in a statement. “The Squad is here to stay, and it’s growing.”

Massachusetts Rep. Ayanna Pressley, one of “The Squad’s” founding members, views the inroads being made by Black progressives as a sign that the Black Lives Matter movement, which has surged in popularity over the last month, is beginning to expand its power.

“What (their success) means is that we’re moving in the right direction. What it means is that when people offer the rallying cry and use the hashtag and like and retweet ‘Black Lives Matter,’ that they understand that Black leadership matters, that Black representation matters,” she said, noting that, for all of her home state’s liberal inclinations, she is the first — and only — Black woman to represent it in Congress.

But Pressley also warned against simplistic readings of the recent elections, citing “broad, deep, diverse, multigenerational, multi-racial movements” lined up behind the insurgent leaders. The developments of the last month, she told CNN, were “encouraging,” but should be viewed in a sobering historical context.

“The Birmingham movement was 37 days. The Freedom Rides were seven months. The Greensboro sit-ins were six months and the Montgomery bus boycott was 382 days,” Pressley said. “So we’re just getting started.”

Fighting for a new normal

Bowman, Jones and Kentucky state Rep. Charles Booker all support “Medicare for All” and a Green New Deal, and received endorsements from Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. The New Yorkers campaigned aggressively in their deep blue districts on promises to engage more deeply and, especially among Black voters, comfortably with the daily lives and struggles of their would-be constituents.

In a moment that mixes intensely felt pain with shoots of optimism about race relations in America, those messages — and their ability to deliver them — took on added weight.

“You do not need to translate to Jamaal Bowman what people are talking about when they’re talking about unaccountable policing, when they’re talking about police brutality. You don’t need to translate for Mondaire Jones when you’re talking about housing segregation, educational segregation, and underfunded public housing,” said Sochie Nnaemeka, the New York Working Families Party state director. “You don’t need to translate to Charles Booker when you’re talking about the real needs of black working people in rural communities.”

Like Booker, who is knotted up in a close Kentucky Senate primary with the establishment favorite and fundraising giant, Amy McGrath, a White former Marine Corps fighter pilot, and Cameron Webb, a 37-year-old Black doctor vying for the House seat in Virginia’s 5th congressional district, Jones and Bowman began to receive more national attention as antiracism protests swept across the country in the aftermath of the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

Kendra Brooks, a Black single mother and Working Families Party member elected to the Philadelphia City Council last year, told CNN that the increased attention to racism and police brutality, coupled with the coronavirus pandemic’s disproportionate impact on communities of color, has increased voters’ appetites for more representative government at every level.

“People are realizing that the authenticity that we bring into these fights is very different because we’re coming from lived experience,” Brooks said. “It’s not a thought, it’s not a theory — it’s our real life experience. And at the end of the day, we’re still going to be in the middle of that fight. We can’t put it back. I can’t take off his brown skin or and be something else. That’s who I am.”

In 2018, Wisconsin elected Mandela Barnes to be its new lieutenant governor, making him the first Black candidate in the state’s history to hold the office. Formerly a state assemblyman and Working Families Party board member, his campaign faced constant questions over whether its appeal would translate in the state’s whiter rural regions — issues, Barnes said, rooted in the political class’ tendency to view the Black voters as a monolith whose unique interests can be addressed on-the-fly, if at all.

“I obviously know that every White voter in the state of Wisconsin is not the same,” Barnes told CNN, before discussing the disparate standards applied to Black politicians. “If I were to mix up a dairy cow and a beef cattle, they would get me out of here so fast. They will look at me like I’m unfit for office. Well, we’re talking about actual Black people, the Latinx community, Asian communities, and (other candidates) go out and have these conversations, like, ‘Oh, I’m learning so much.’ The campaign is not the time to learn. You should learn this stuff before you think it is appropriate for you to represent these people.”

Those frustrations, Barnes said, have bred resentment and a growing desire to replace the old guard with more grassroots candidates.

“People who are closest to the challenges, people who are having every decision made about them, and not having a chance to make the decisions for themselves, are kind of fed up with it,” he said, “because we’ve been ill-served as a result of people spending their entire political careers trying to figure us out.”

Shaping the narrative

The increased attention being paid to Black Americans’ experiences in the midst of a nationwide anti-racist uprising has offered candidates of color a rare opportunity to address issues affecting their communities in more depth, more frequently and to larger audiences, Collective PAC founder and executive director Quentin James, told CNN.

That exposure benefited the Black candidates on the ballot this week, he said, and helped speed up an evolution among progressives who are desperate to build winning coalitions on a wider scale.

“The new populism in this country is one around racial inclusion and racial authenticity. Some of the White candidates still struggle with the racial analysis,” James said. “That was a major problem with the Sanders campaign. We could be with you on a lot of different issues — health care, education, the economy — but if you don’t understand race and understand the racial analysis that’s needed, and intersectionality, then you’re probably not going to be successful.”

Jones told CNN that he expected to win his primary in New York before Floyd’s killing touched off protests across the country. And though he is pleased that the reckoning that followed has caused some Americans to examine issues of racial injustice they had previously ignored, Jones expressed concern that his success, and those of other Black candidates, would diminished the efforts of a campaign that began last year.

“What I’m worried about is this narrative, that I’m sure my opponents believe, which is that the reason we won is because everyone was just distraught because there’s racial inequality in this country,” he said. “And that does a great disservice to the work that we’ve been doing to be victorious.”

As for the potential that he, too, might face a primary challenge in a couple years, Jones was untroubled — and suggested he would welcome another round with one of his 2020 rivals.

“Adam Schleifer can come back at me because he has infinite wealth. He could try to run against me and he’ll lose again,” Jones said. “But even if he were a more compelling candidate, I would still not be worried about it because I am confident that I’d be offering the best representation that anyone could possibly be providing my constituents. And that’s all anyone who doesn’t feel entitled to a seat could ever expect.”